Period:

Second World War

Region:

Hungary

The Hungarian camp Sárvár - WW2

The Sárvár camp is one of the concentration camps established by the Hungarian fascist authorities on their territory for Serbian prisoners, who were brought from the territory of the occupied Kingdom of Yugoslavia, more precisely, from the regions of Bačka and Baranja.

This death casemate was situated in the far west of Hungary in Vaš county in a former silk factory from June 1941 to March 1945 when the Red Army liberated Hungary in its campaign to Berlin.

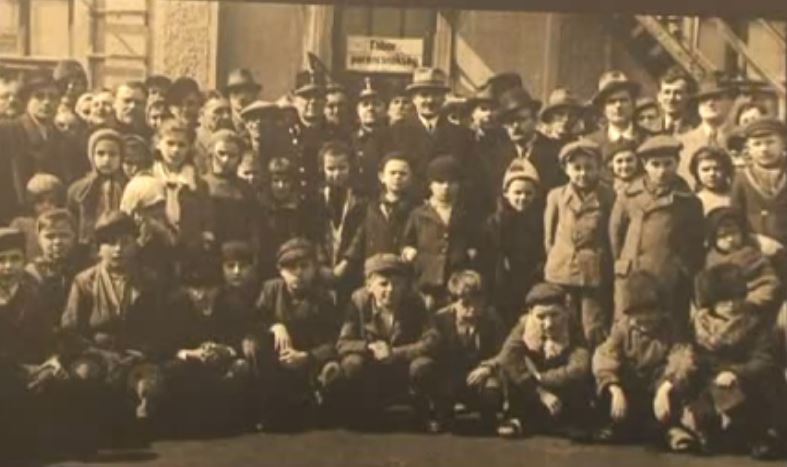

According to current information, around 15,000 people passed through the Sárvár camp, more than 95% were Serbs, while the rest were Slovenes from Lendava. Prisoners of all ages, women, and children, were there.

In the occupied Bačka, Hungarian fascists arrested all Serbs including members of the Sokol societies and colonists who had not lived there before October 1918, and forcibly took them to their concentration camps with the aim of exterminating Serbs in Vojvodina including Sárvár. Whole families were taken away.

The post-war communist authorities never asked the Hungarian authorities to extradite criminals who were known by names to have committed crimes, both in Vojvodina and in the Hungarian camps, three of them, according to current information.

A monument for the martyrs of the Sárvár camp was erected in the cemetery in the 1960s, where a memorial plaque was also placed.

BACKGROUND

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians, the first South Slavic state, later renamed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, was created after the First World War, with its promulgation on December 1, 1918, in Belgrade. The territory of the Yugoslav Kingdom was divided into banates in 1929 and the structure of its government was a parliamentary monarchy.

Proclamation of the first South Slavic state

The royal title was held by the Serbian Karadjordjević dynasty. It consisted of Southern Serbia, Šumadija, Raška, Kosovo and Metohija, Eastern Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Vojvodina, Slavonija, a small part of Dalmatia, the Dubrovnik Republic, Lika, Kordun, Banija, Zagorje, Gorski Kotar, and Slovenia.

After the assassination of King Alexander I Karadjordjević in Marseilles on October 9, 1934, the country was ruled by regents: Prince Paul Karadjordjević, Dr. Radenko Stanković, and Dr. Ivo Perović, and the government was formed by Dragiša Cvetković and Vlatko Maček.

Belgrade's demonstration on March, 1941.

In the mid-1930s, Europe witnessed the rise of Nazism and Fascism, especially in Germany, Italy, and Spain. This led to the formation of the Tripartite Pact, on September 27, 1940, between Germany, Italy, and Japan. In the next months, this alliance was joined by the following countries: Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, etc. Thus, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia found itself surrounded by Axis Powers.

In Vienna, on March 25, 1941, the signing of the protocol between the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Nazi Germany took place regarding the passage of German and Italian troops through Yugoslav territory. Among the patriotic forces of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, this was interpreted as treason, and the British and Soviet intelligence officers organized a military coup and demonstrations on March 27, 1941 in Belgrade resulting in the overthrow of the governorship led by Prince Paul and putting on the throne a minor king Petar II Karadjordjević.

Hitler changed the plans and the armed forces' plans to attack Greece, were diverted to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE CAMP

The camp in Sárvár was established in the far west of Hungary in Vas county, along the border with Austria, 190 km west of Budapest and 375 km northwest of Novi Sad. Its official name was “Hungarian Royal Camp for Internment ”.

This death camp was established at the end of June 1941 by order and knowledge of the highest authorities of fascist Hungary: the Government, the National Assembly, and the Presidency.

The detainees were brought in from the occupied territories of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the northwest parts of the Danube Banovina, which included Bačka and Baranja.

In fact, the Hungarian occupation authorities, on the order of the Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy, a fascist leader in the service of Adolf Hitler, started killing (estimated at more than 3,500 Serbs) and arresting all those they considered “colonists”, i.e. those who came to the territory after 31 October 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian era in those parts ended.

The result of the Hungarian cleansing in Sombor, April 1941

The Proclamation of the Hungarian occupation army issued by General Ferenc Bajor on 25 April 1941, read as follows:

- ”All those persons of Serbian, Gypsy nationality, and further, Jews, who before 31 October 1918 had not had a municipal homeland in the territory of Greater Hungary (excluding Croatia), and are not descendants of such persons, i.e. immigrants or colonists, are obliged to leave the territory of the state within three days, beginning 29 April 1941 at midnight”

The Hungarian occupation authorities also forcibly expelled Serbs from Bačka by sending them under guard to Srem, from where the Ustashas returned them.

After expelling them from their homes, Hungarians placed the remaining Thessaloniki volunteers and their children in about 40 concentration camps throughout Bačka and later transported them in cattle wagons to Sárvár.

CAMP CONDITIONS

Like any other concentration camp, the one in Sárvár was horrible because it was dirty, and the inmates did not have adequate medical care.

The camp was built around a former silk factory which had been reconstructed to intern the unfit.

Beatings and torture by the camp guards were the everyday routines of the Sárvár inmates. Food rations were scarce, bathing was also denied… so dysentery and other diseases were common among Serbian inmates. Lice and itching also prevailed.

The inmates were placed in cells with the so-called boxes, one above the other. There was one family in one box, and another one in the box above.

The small Serbian community in Hungary during World War II sought to help their compatriots detained in camps. Humanitarian aid was organized, primarily done by Serbs from Pomaz near Budapest. Some Serbs stayed in Hungary after they had been released from the camps.

In 1942, the Bishop of Bačka, Irinej Ćirić, led an action to save Serbian children from the Sárvár camp; then, the Hungarian military authorities allowed 2,812 children under the age of 15 (188 infants and 184 nursing mothers) to leave the camp and go to Bačka, where they were put in foster families. In this way, they were saved from certain death.

TESTIMONIALS

Ljubica Ćurčin (born 1935), a survivor of the Sárvár camp, says the following about these horrible days:

- “Death was our constant companion, dying every day, in wooden beds without rugs, in the camp yard, in a dump we dug up in search of food leftovers...

Hunger, dysentery, typhus, and tuberculosis mostly killed children, so in 1942 my three-year-old sister Bosiljka died there…”.

A historian dr Milan Micić says the following about the Sárvár deportations:

- “The repression of the Serb population of Bačka in World War II, especially of the Serb volunteers from World War I, was an act of punishing ‘traitors’ from World War I...

When you talk to people in Rastina, Bajmok, Karađorđevo, Aleksa Šantić, Sirig, which are all colonial settlements that emerged between the two world wars, there is hardly any family there that does not bear the mark of Sárvár. The fate of Serbian colonist families from Bačka has marked their national identity for good.”

A silk mill in Sárvár where Serbs were detained

Kosta Hadži Jr., whose father, a famous lawyer from Novi Sad, led the action of saving the Sárvár prisoners and in 1970 received the Order of Merit for the People from the President, says the following:

- “The first humanitarian action was in 1941 when the authorities persecuted Jews, forcing them down Pašićeva Street in Novi Sad. My father was there with several intellectuals; they hastily picked up some food cans and gave them to the Jews. They were temporarily expelled to Sajlovo from where their trace was lost.

My father carried out the Sárvár action with the help of Bishop Irinej Ćirić who was a member of the Hungarian Senat. The action was successful in fulfilling two conditions imposed by the Hungarian authorities. The first condition was that those who were released from the camp cannot return to their properties because Hungarians lived there. The second one banned former prisoners from engaging in politics.

There were very smart and skillful craftsmen among the detainees, so one of them made a cigarette case for my father with the image of the Kosovo hero Miloš Obilić at the back and my father’s name written inside. Under the name, there was a nickname that the detainees gave themselves - “Šarvarci”- Sárvárians. They gave the cigarette case to my father because they had not forgotten him…”

Jovan Dejanović, former mayor of Novi Sad in the 1980s, tells about his camp days in Sárvár tt an exhibition about the Novi Sad Raid in 2014:

- “I had scabies, lice, and was very ill. Everyone in the camp got their ration of 20 decagrams of bread and my mother gave up her share for three months to give it to me so that I could survive.

The camp was terrible! Only 14-year-old boys could leave the camp with transports to Bačka. It was in May 1942, and I was 15 in June, and no one who was 15 could leave with the transport. That difference of one month saved me.

Just imagine how life can fix such circumstances: later, I was a socio-political worker and in 1984 I went on an official visit to Hungary. As is usual in diplomatic protocols, the hosts ask me, since I have the treatment of the highest rank guest, what I would like to add to my schedule privately, if I would like to visit a special place while in Hungary. I said that I wanted to visit the former Sárvár camp because I was imprisoned there during World War II.

The Hungarians fulfilled my wish. I was greeted by a whole “suite” in Sárvár. I planted a tree near the monument in the camp and when the hosts left me alone for a moment, eh, I just gave myself a breather and had a good cry.

When I went back to Bačka, I was placed with Mogin Mladen who was a top craftsman for making carriages…”

Stana Rončević, born in 1935, a survivor of the Sárvár casemate, says the following:

- ”I was only five, but even today I see horrible images of being forced out of my native Rastina. They took us straight to the camp in cattle wagons with around a hundred souls squeezed in each one, and they never opened the wagons for the two days and two nights that the journey lasted.

There they were greeted by guards with rifles and whips, the halls of a former silk factory with hastily made wooden bunk beds barely 40 cm wide and with no mats, and by the cold and hunger I cannot forget for the rest of my life…”

Milan Korać, a Sárvár camp survivor who spent a year there when he was 13, says:

- “The winter of 1941-1942 was terrible and 100 grams of moldy bread and soup of fodder beet or rotten cabbage was our only meal, so we were overwhelmed to find half-rotten potato peels in the camp garbage dump.

At least four or five children died every day, adults were forced to work to exhaustion on the surrounding farms...

More than 850 souls died in the camp from hunger, dysentery, typhus, and tuberculosis, and soon after the liberation, hundreds more suffered the fatal consequences of the terrible Sárvár years.

As Hungarian gendarmes and soldiers were throwing us out of our houses in Sokolac, Hungarian civilians from the neighboring Stara Moravica were waiting at the village entrance to break into and rob them. Later, the houses and farms of the Thessaloniki volunteers were given over to Hungarians who immigrated from Bukovina and Erdelj.

When my family reunited in Sokolac in 1945, we found only the remains of the demolished house. There was nothing in the ones that remained intact, not even the doorknob…”.

CLOSING OF THE CAMP

The Sárvár camp worked unhindered throughout World War II. Only when the Soviet Red Army units defeated the fascist regime in Hungary on their way to Berlin in 1945, did this casemate of death ceased to “work”.

More precisely, battles for the liberation of the camp were fought. Officially, the camp was liberated on 28 March 1945 and the torture of Serbs ceased.

YEARS LATER

There is a memorial complex built in Sárvár that consists of a cemetery where camp prisoners were buried and a monument which was also made in the 1960s for the victims of the casemate. Delegations of Serbs from Bačka came here to visit the monument and lay wreaths.

The residents of Sárvár maintain the cemetery now.

Former prisoners from the Sárvár death casemate, 200 of them, tried to get war compensation from Hungary twice, but they did not succeed, not even a symbolic compensation. The first time was in 1996, and the second about ten years later.

The Supreme Court of Hungary reasoned that the prisoners did not have Hungarian citizenship at the time.

PUBLICATIONS

There are several works published about the horrors of the Sárvár camp.

One of them is certainly the book “Serbs in Camps of Hungary 1941-1945” by Danilo Urošević who was interned with his family from Bajmok and managed to survive as a boy during the days of the Golgotha. His book was published in 2014 in Hungarian and Serbian by the Serbian self-government in Budapest and the Archives of Vojvodina in Novi Sad.

In 2009, the journalist of the Novi Sad Television, Laslo Tot, made a one-hour documentary film “Angels from the Mud Fortress”, with the Sárvár camp as the main part of the story in which the survivors of the horror talk to the camera. The documentary was filmed with the production assistance of the Province Secretariat for Culture and the Association of Film and TV Workers of Vojvodina.

Tags:

Please, vote for this article:

Visited: 4394 point

Number of votes: 61

|