Period:

Second World War

Region:

ISC

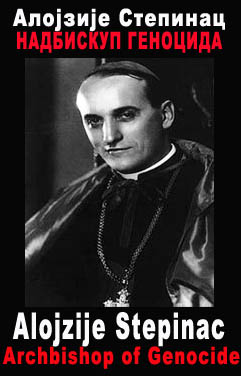

The Croatian archbishop and criminal- Aloysius Stepinac

Aloysius Stepinac (1898-1960) was the Archbishop of Zagreb and a Croatian cardinal, who decades after his death became a beatus of the Roman Catholic Church.

He participated in the mass conversion of Orthodox Serbs to Catholicism, i.e. Croats on the territory of the Ustasha Independent State of Croatia during the Second World War.

He had a good relationship with Ante Pavelić from the beginning of his rule and also was aware of many crimes against Serbs, namely the existence of concentration camps in which mostly Serbs were tortured, but he did nothing to prevent them.

During 1941-1945, the Vatican, that is, the Roman Curia provided him with great assistance in the conversion of Serbs.

In 1946, the Yugoslav communist authorities convicted him of collaborating with the Ustashas, and he later spent the rest of his life under house arrest and in prison.

The new Croatian authorities, led by Franjo Tudjman and the HDZ party during the 1990s saw Stepinac as a saint and martyr.

BIOGRAPHY

Aloysius Stepinac was born on May 8, 1898, in Krašić, near Zagreb, in a comparatively wealthy peasant family. His father Josip had twelve children, four from his first marriage and eight from his second marriage. Aloysius completed elementary school in his hometown and high school in Zagreb. When he finished the sixth grade of high school, he entered the archdiocesan lyceum with a serious intention to dedicate himself to the priestly vocation.

He was very suddenly drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army in 1916. He was able to pass the eighth grade and graduate in a short time, and then he traveled to Rijeka to a priest's school. He soon found himself on the Italian front as a new officer, but his military career was soon brought to an end by being wounded in the battles on Sochi and Piava.

Many of Stepinac's biographers mention his prudence and courage as an officer, however, there is no material evidence for such claims.

During World War I, his parents had no news of him. The news then reached Krašić that their son had died somewhere in Serbia, and his belongings were sent to them.

Stepinac had been captured and taken to an Italian military prison. From there, he managed to escape and join the Army of the Kingdom of Serbia as a volunteer on the Thessaloniki front, where he remained until the spring of 1919 when he was demobilized as a lieutenant.

In the same year, Stepinac enrolled at the Faculty of Agriculture in Zagreb.

During his studies, he joined the Academic Catholic Society Domagoj. He remained in studies for only a year, after which he returned to his father's estate, where he worked for the next few years.

Stepinac also met his great love, teacher Marija Horvat, whom he eventually proposed to. However, although she initially accepted the marriage offer, Marija Horvat later changed her mind and returned his engagement ring.

PRIEST'S CALL

How he happened to finally decide to become a priest, one can only guess. He had found himself in Rome in 1924, on the recommendation of the rector of the Zagreb Seminary, Dr. Josip Lončarić. After receiving an American scholarship, he completed philosophy and theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University after seven years and did two doctorates. There he learned to speak and write Italian, French, German, and Latin.

Upon his return to Zagreb, the young Jesuit protégé Stepinac was admitted to the Archbishop's office, and then appointed master of ceremonies of the Archbishop, Dr. Ante Bauer.

Soon after, the seriously ill Archbishop Bauer asked the Vatican to assign him a coadjutor with the right of inheritance of the Zagreb archbishop's chair. Stepinac was completely unknown in Croatia. The proposal for it to be Aloysius Stepinac, and then the decision to appoint him - resonated at Kaptol as a big surprise.

Serious criticism by competitors, as well as other members of the high Catholic clergy, was directed at the Yugoslav episcopate as well as Vatican figures, primarily Pope Pius XI and his Papal Secretary of State Maria Pacelli, the future Pope Pius XII. However, it all ended there, because the Vatican seems to have needed a young and determined fighter, who will be able to respond to the demands of the Roman Curia.

That is how Stepinac became the head of the Episcopate during Bauer's lifetime, on May 28, 1934. After Bauer's death, the young Stepinac took over the administration of the Zagreb Archdiocese on December 7, 1937.

Stepinac's qualifications helped the work on his appointment to be completed faster. As the consent of the Yugoslav government was needed at the time regarding his appointment, King Alexander I Karadjordjević agreed, knowing that Stepinac was a volunteer on the Thessaloniki front, and believing that it was also an expression of his Yugoslav commitment. Stepinac's volunteering will never be mentioned again after this, it will even be claimed as untrue.

As the Archbishop of Zagreb, Aloysius Stepinac strongly opposed the refusal of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to sign the Concordat with the Vatican, so he turned to the Croatian opposition.

He was especially indignant at the British spies who opposed the accession of the Yugoslav kingdom to the Triple Alliance, which carried out a coup d'etat in Belgrade and overthrew the governorship of Prince Pavle Karadjordjević on March 27, 1941.

WORLD WAR 2

From the first days of the Second World War, the Archbishop of Zagreb, Aloysius Stepinac, wholeheartedly blessed the creation of the "new Catholic state", as he often called the Independent State of Croatia.

On April 12, 1941, he met with the general of the Ustasha army, Slavko Kvaternik, after the proclamation of the Independent State of Croatia.

Archbishop Aloysius Stepinac met for the first time with Ante Pavelić immediately after his return on April 16, 1941, four days after the proclamation of the Independent State of Croatia, and expressed full support for the newly formed Ustasha state.

On Easter 1941, Stepinac re-announced the formation of the Independent State of Croatia, and on that occasion, on behalf of the Vatican, he blessed the Ustasha leader Ante Pavelić. Then, among other things, he said:

"While we cordially greet you as the head of the Independent State of Croatia, we ask the God of the Heavens to give his heavenly blessing to you, the leader of our people."

As early as April 28, 1941, Stepinac wrote a "pastoral letter" in which he called on the friars and priests to support and defend the new Catholic state of Croatia.

Close associates- Stepinac and Pavelić

Immediately upon the establishment of the government, the home guards (domobrani) and the Ustashas started realizing their plans for the liquidation of the Serbian population, which Stepinac must have been aware of because executions were carried out publicly.

With the consent, and under the supervision of, Abbot Josip Ramir Markone, the papal legate in the Independent State of Croatia, Aloysius Stepinac convened a new Bishops' Conference in Zagreb from November 17 to 20, 1941, which was dedicated to the conversion of Orthodox Serbs to the Catholic faith.

In those conversions, Stepinac allegedly saw the rescue of Serbs, Jews, and Roma from the Ustasha knife.

In a letter to Pope Pius XII, dated May 18, 1943, Aloysius Stepinac states that at least 250,000 Orthodox Serbs were converted in the Independent State of Croatia. Conversions were coercive because many Serbs had no choice: they could be either converted or killed. Many of them were killed, despite being converted.

Stepinac's speech regarding the Ustasha massacres took place at the beginning of 1943.

At that time, in revenge, the Ustashas shot 30 peasants from his native village of Krašić, including his brother Maksim, without Stepinac knowing it.

He spoke at a sermon in the Zagreb Cathedral and raised his voice against such crimes. According to the documents, these protests were made under pressure from the Vatican, which in 1943 already assumed the outcome of the war, that is, the defeat of Hitler's coalition.

From the Vatican, the idea was pushed through Stepinac to later change the Ustasha government in Croatia and bring Maček's party HSS to power, which would allow Croatia (as an allegedly anti-fascist country) to keep the borders of the NDH.

There is the testimony of Vaso Kondić from the village of Sladinja in Podkozara, who was detained in the Jasenovac death camp as a seven-year-old. He saw in 1941 that Stepinac not only came to the camp but also witnessed the killing of the children of Serbs and Jews.

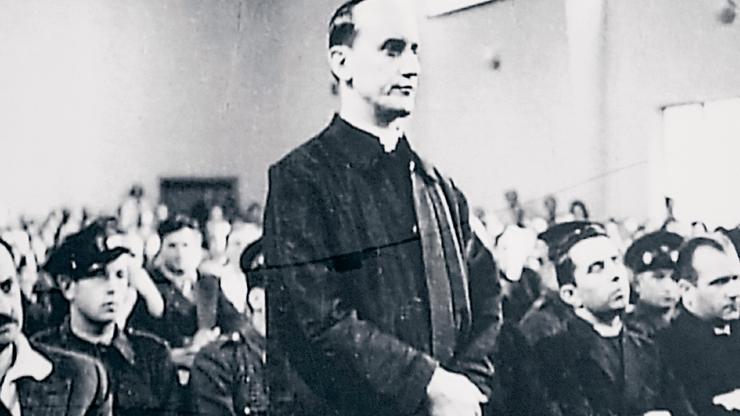

Aloysius Stepinac on the right, 1944

Archbishop Stepinac was fully aware of the existence of the Jasenovac concentration camp, but he did not publicly oppose it. As the end of the war approached, Stepinac was most reluctant to win the communists, so he completely agreed with Pavelić's line.

He did not want to flee to Austria but stayed in Zagreb. Immediately after the liberation of Zagreb in 1945, Josip Broz Tito arrived and spoke sympathetically with the leaders of the Catholic Church on July 2, 1945.

At the same time, Tito promised that the new government would not do anything without an agreement with the Roman Catholic Church. Vladimir Bakaric also attended these talks. The tolerant relationship between the new government and the Catholic Church was short-lived. In particular, problems began to erupt over the secularization of church property and the abolition of religious education in schools.

ARREST

Aloysius Stepinac was first arrested on May 17, 1945. He was detained on Zagreb's Mlinarska Street, where the Ustasha prison from the time of the Second World War was located. The interrogation and detention lasted until June 3, 1945, when Stepinac was released.

A day later, Aloysius Stepinac and Josip Broz Tito had a long telephone conversation, which Stepinac characterized: "We talked like men." Tito and Stepinac did not agree on anything. Stepinac publicly criticized the government because it confiscated the property of Catholic priests and expelled some of them. Relations with the authorities were further strained.

Aloysius Stepinac protested with his bishops in a pastoral letter dated September 20, 1945, where he expressed the state's objections to the church. Stepinac was then in a bind, because on the one hand he had to give in to the state government, and on the other hand, he did not want the separation of the Catholic Church from the Vatican.

Relations between Stepinac and the new authorities became even more complicated in July 1946. At that time, Stepinac's apartment was under blockade and he was being held under some kind of house arrest.

Stepinac could only get away by supporting the new communist government in Croatia. Stepinac did not do this but continued to criticize the government. He was arrested for the second time on September 18, 1946. He was brought before the Supreme Court of the People's Republic of Croatia.

TRIAL

The trial of Aloysius Stepinac and the other fifteen friars, including Erih Lisak and Ivan Salic, was held before the Supreme Court of the People's Republic of Croatia from September 9 to October 11, 1946, in the hall of the gymnasium in today's Tkačićeva Street in Zagreb.

The trial was presided over by Judge Dr. Zarko Vimpulsek, and the members of the panel were: Dr. Antun Cerinec, Ivan Poldrugac, and Ivan Pirker; the indictment was represented by Jakov Blažević and the recorder was Dr. Ante Petrović. Aloysius Stepinac was defended by Zagreb lawyer Zdravko Politea, who had once represented Tito at the "bombing process".

In short, Stepinac was accused of collaborating with the top of the Ustasha state, meeting with Pavelić and other Ustasha officers, of converting tens of thousands of Serbs, of incitement given to the Ustashas by the Catholic clergy, of speeches encouraging prayers for Pavelić and of anti-national action after the war.

He defended himself with silence. At the end of the hearing on October 3, 1946, Stepinac broke his silence and gave his famous speech. Stepinac called the christening of Serbs an incorrect expression because it was a religious conversion of already baptized people.

In his closing remarks, Stepinac reiterated that he was innocent of all charges and that history would evaluate his work. The verdict was passed on October 11, 1946. Only Erich Lisak and Salic were sentenced to death and all the others to time sentences.

Aloysius Stepinac was sentenced to 16 years in prison with forced labor, loss of political and civil rights for 3 years, and later his sentence was commuted to house arrest in his hometown of Krasic in Zumberak.

PRISON AND DEATH

After the verdict was pronounced, Aloysius Stepinac was taken to serve his sentence in the Lepoglava prison, near Zagreb. He remained there until December 6, 1951. Voices of indignation came from different directions.

Roman Catholic dignitaries, Croatian writers, and writers agitated the most for the release of Stepinac. In such circumstances, Tito's government gave in.

Thus, on behalf of the communist authorities, Dr. Vladimir Bakarić visited Stepinac in Lepoglava as early as March 1947. He asked him to sign the already drafted petition to the President of Yugoslavia, J. B. Tito for pardon, assuring him that he would be released immediately and sent abroad. Aloysius Stepinac refused.

He even demanded that the judicial process be resumed, but not in the communist judiciary. In the meantime, due to his poor health, he was interned in his native Krasic, where he was guarded by UDB agents in front of his house until his death.

New moves by the Vatican followed. On November 29, 1952, Pope Pius XII appointed 14 new cardinals, including Archbishop Stepinac. Yugoslavia responded with a countermeasure by severing all diplomatic relations with the Roman Curia on December 12, 1952.

While in custody in Krasić, Stepinac unexpectedly grew sick. He felt worse every day. There have even been speculations that he was poisoned in prison.

Doctors found him suffering from a very rare disease, an abnormal increase in erythrocytes. There was no cure for this disease.

He died on February 10, 1960, in his family home. The body of Aloysius Stepinac was buried in the Zagreb Cathedral according to the canonical custom. The poet Lucijan Kordić eulogized him at the ceremony.

STEPINAC'S CULT

As soon as the militant party HDZ came to power in FR Croatia in mid-May 1990 and Franjo Tudjman became president, the Croatian Catholic Church allied with it and thus speculation about the violent death of Cardinal Stepinac was renewed.

The trial against Stepinac was declared a rigged against the Croatian people and the Roman Catholic Church by the communists.

A large number of books and public works about Stepinac were published. Many details from his life were sought for Aloysius Stepinac's personality to rise on the pedestal of a martyr of the faith and be beatified. There were even stories of Stepinac taking part in saving Jews from the Holocaust.

It was rumored that the archbishop had been poisoned with oleander tea for exactly 1,864 days, although an autopsy after Stepinac's death in 1960 showed that the archbishop had died as a result of severe kidney inflammation.

In 1993, a new autopsy was performed and led to allegedly startling discoveries. One of the most morbid allegations is the rumor that there was no heart in the body during the second autopsy.

Pope John Paul II proclaimed him "blessed" in 1998, which immediately precedes canonization.

Tags:

Please, vote for this article:

Visited: 9536 point

Number of votes: 39

|